In early 2022, I had the great privilege of taking part in a field methods course taught by Dr. Jordan Lachler of the Canadian Indigenous Languages and Literacy Development Institute (CILLDI) in which the language being discussed was Sango, a creole language spoken throughout the Central African Republic. As my term paper, I wrote a descriptive analysis of colour terminology in Sango, based on experimental results from our wonderfully patient Sango language consultant, Robby Kongolo. Although the results were quite interesting (at least, to me), the participant pool size of one largely precludes me from making any authoritative statements on the validity of the data. However, for any interested parties, you can find my term paper here

Background

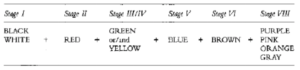

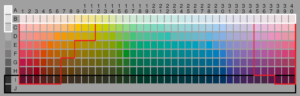

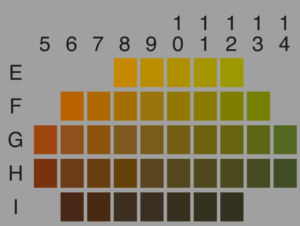

Academic interest in linguistic colour categorisation has been attested since at least the early 20th century in synchronic studies (Rivers 1901), and even earlier diachronically (Gladstone 1858; Sampson 2013). However, it was the 1969 publication of Brent Berlin and Paul Kay’s seminal work Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution that is often seen as responsible for the intensity of modern investigation into colour terminology as an area of cross-linguistic semantic comparison (Saunders 2000). Berlin & Kay (1969) posited that basic colour terms, or BCTs, (which they defined as colour terms which are monolexemic, unrestricted in referent types, psychologically salient, and not subordinate to any other colour term) arise in all languages in discrete, chronologically ordered steps along a universally shared hierarchy, with languages beginning with only BCTs for ʙʟᴀᴄᴋ and ᴡʜɪᴛᴇ, then developing a term for ʀᴇᴅ, then a term for either ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ or ɢʀᴇᴇɴ, then whichever term was missed in the previous step, then ʙʟᴜᴇ, then ʙʀᴏᴡɴ, and then ᴘɪɴᴋ, ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ, ɢʀᴇʏ, and ᴏʀᴀɴɢᴇ in random succession. This evolutionary chronology is demonstrated in Figure 1:

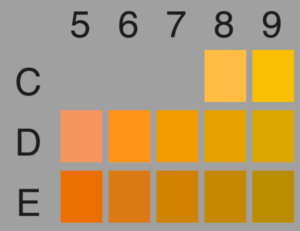

Figure 1, the developmental sequence of BCTs according to Berlin & Kay (1969)

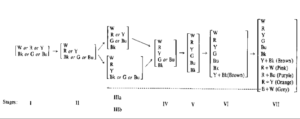

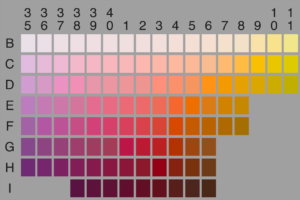

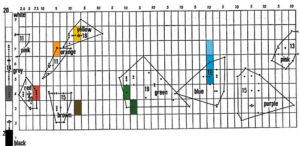

Further theoretical refinements to BCT theory were made by Kay & McDaniel (1978), who proposed the existence of ‘composite categories’, that is, BCTs whose boundaries are fuzzy unions of one or more of the six ‘primary’ colours (black, white, red, yellow, green, and blue), among other minor sequential adjustments to the evolutionary chronology. Additional developments were made in the World Color Survey (Kay et al. 2009), which surveyed groups of monolingual speakers (with a mode sample size of 25) of 110 unwritten languages from non-industrialised societies on five continents, resulting in further revisions to the developmental chronology:

Figure 2, a revised model of the developmental sequence of BCTs, as presented in Kay & McDaniel (1978)

Historically, much of the work of Berlin, Kay, and others has focused on the utility of BCTs to prove theories of linguistic universals and to variously support and detract notions of linguistic relativity, both applications which have garnered substantial methodological criticism (Levinson 2001; Lucy 1997). However, few dispute the utility of thorough investigation into colour terms from the perspective of linguistic documentation; being that colour as a physical phenomenon is experienced in some form or another by all sighted language communities, understanding the various linguistic strategies at play regarding colour description can provide invaluable insight as to the cultural relevance placed by language communities on individual aspects of their physical environment, as well as to the morphosyntactic means by which semantic descriptors are encoded in a language. It is in this latter capacity, the pale of documentarianism, that the following colour term study of Sango (ISO:sag) has been undertaken.

Sango, a French-influenced creole of various Ngbandi languages spoken by over 1.6 million people throughout the Central African Republic, has long lacked any extensive colour term documentation, with the exception of its 2021 inclusion in a typologically balanced sample of 401 African languages used to study areal patterns in colour term colexification (Segerer & Vanhove 2021). The only evident documentation of Sango colour terms appears to be in the form of various bilingual dictionaries, such as Charles Taber’s A Dictionary of Sango (1965), William Samarin’s A Grammar of Sango (1963), and SIL’s Mini Dictionary of Sango (2017). However, these resources have (necessarily) documented Sango colour terms only in the context of direct, lexical translation, lacking any visually-defined boundaries, and in any case present only a handful of colour terms each. Thus, in addition to its novel experimental data, the following study intends to serve as a centralised repository for currently documented Sango colour terminology, defined by both lexical and visual means.

- Methodology

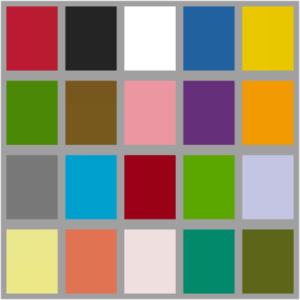

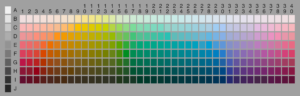

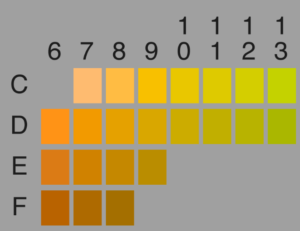

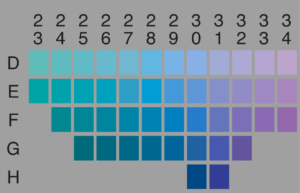

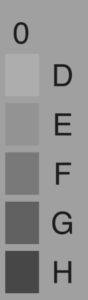

Much like the initial BCT studies of Berlin & Kay, we made use of a 330 colour Munsell Palette, consisting of a grid of forty equally spaced hues at maximum saturation, each with eight different degrees of brightness, as well as ten neutral hues ranging from white to grey to black. Firstly, our single participant, a male native speaker of Sango and Yakoma who was also fluent in French and English, was shown twenty colour chips from the Munsell Palette (of which 11 were known cross-linguistic focal points for BCTs, and 9 were randomly selected) and asked to provide the first Sango term that came to mind to describe the colour depicted by that chip. After this, they were shown the full Munsell Palette and asked to indicate the maximum possible extension of each colour term which they had named in the first section; that is, for each colour term (basic and otherwise), they were asked to mark every possible chip which could, under any circumstances, be described by the given colour term. In addition, for each colour term, they were asked to mark on the palette a focal point, that is, a single chip which best represented the colour term as a whole. This process was carried out digitally over a Zoom conference call, with the participant indicating the colour term boundaries on the palette via Microsoft Paint.

Figure 3, the 20 semi-random colours used in the first section of our investigation, with Munsell co-ordinates (from the top left, left-to-right) being G2, J0, A0, G30, C10, F15, G8, D0, H34, D7, F0, E28, H3, E15, C22, B12, E3, B1, F19, and G13

Figure 4, the 330 colour Munsell Palette used in our investigation

- Results

3.1 Sango Basic Colour Terms

Sango, on first examination, appears to have three basic colour terms, being vukö (ʙʟᴀᴄᴋ, or more generally, ‘dark’), vurü (ᴡʜɪᴛᴇ, or more generally, ‘light’), and bengbä (ʀᴇᴅ). This system corresponds to the expectations of a Stage II language in Berlin & Kay’s BCT chronology (1969), as well as bearing similarity to the trinary BCT distinctions of other Ubangian languages, such as Mündü in South Sudan, and of other Niger-Congo languages in Central and Western Africa more generally, such as Gunu and Ejagham (Kay & Maffi 2013). Sango’s three basic colour terms can all appear both adjectivally (vukö, vurü, bengbä) and verbally (avûko, avuru, abe). Of these, avûko and avuru can also be used as modifiers indicating the brightness of other colour terms (i.e. abe avuru (‘light red, pink’) or abe avuko (‘dark red’)). Aside from vukö, vurü, and bengbä, Sango colour terminology is generally composed of periphrastic constructions consisting of multiple lexemes (often with one of the three BCTs as the head verb in these constructions, as is outlined throughout Section 3.2), and of metaphorical comparisons with varying degrees of apparent psychological salience; all characteristics disqualifying such terms from BCT status, and defining them instead as derived (that is, non-basic) colour terms.

Figure 4, the maximum possible ranges for avûko/vukö, avuru/vurü, and abe/bengbä according to our informant.

This visual distribution of Sango’s three BCTs aligns closely with the expected ranges of ʙʟᴀᴄᴋ, ᴡʜɪᴛᴇ, and ʀᴇᴅ in a Stage II language according to Berlin & Kay (1969), albeit with vukö and vurü having slightly more constricted distributions among shades of blue and green, as is demonstrated in Figure 5:

Figure 5, “Typical Stage II Basic Color Lexicon” from Berlin & Kay (1969)

3.1.1 Vurü/Avuru (ᴡʜɪᴛᴇ)

Vurü/avuru (translated by the Taber dictionary (1965) as “white, clean”), corresponds to the BCT category of ᴡʜɪᴛᴇ, having a distribution which includes the same focal point as the English ‘white’ (A0), several light greys, and the entirety of Row B on the Munsell Palette. Thus, vurü/avuru spans a diverse variety of pale, coloured hues in addition to brighter monochromatics. According to Berlin & Kay (1969), this distribution is fairly typical of Stage II languages with 3 BCTs (see Figure 5):

Figure 6, the maximum visual range of vurü/avuru, with the focal point located at A0

The verbal form avuru was frequently used as the basis for derived colour terms using the construction avuru töngana… (‘[it] is vurü like …’); although our informant gave only two examples, avuru töngana gozo (‘[it] is vurü like cassava’), which referred to any pale beige, and avuru gï kêtê (‘[it] is only slightly vurü’), which referred to any non-monochromatic shade of vurü, the Sango translation of the Bible (SBC 2010) provided several others, as well as examples of vurü/avuru’s usage in referring to pale hues in general:

- fade ayeke kiri ti vuru tongana tukia

ғᴜᴛ SM+be return ʟɪɴᴋ white like snow

“they shall be as white as snow” (SBC 2010 Isaiah 1:18)

- kua ti li ti lo avuru tongana kua ti tere ti taba

hair ʟɪɴᴋ head ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG SM+white like hair ʟɪɴᴋ body ʟɪɴᴋ sheep

“the hair of his head was white like wool” (SBC 2010 Daniel 7:9)

- pembe ti lo avuru ahon ngu ti me ti bagara

tooth ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG SM+white exceeding liquid ʟɪɴᴋ breast ʟɪɴᴋ cow

“his teeth whiter than milk” (SBC 2010 Genesis 49:12)

- kua ti tere ti lo abe kete si avuru kete

hair ʟɪɴᴋ body ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG SM+red slightly and SM+white slightly

“a yellow thin hair” (SBC 2010 Leviticus 13:30)

- fade ala sara titene mbi so kua ti li ti mbi avuru kue awe so

ғᴜᴛ 2PL do so that 1SG ʀᴇʟ hair ʟɪɴᴋ head ʟɪɴᴋ 1SG SM+white all ᴘᴀsᴛ ᴅᴇᴍ

“you will bring my gray head down” (SBC 2010 Genesis 42:38)

- tere ti ala avuru aza tongana têne ti safir

body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+white SM+shine like matter ʟɪɴᴋ sapphire

“the beauty of their form was like sapphire” (SBC 2010 Lamentations 4:7)

3.1.2 Vukö/Avûko (ʙʟᴀᴄᴋ)

The Sango term vukö/avûko, translated by the SIL dictionary (2017) as “black, dark”, corresponds to the BCT category of ʙʟᴀᴄᴋ, having a focal point at J0 (the same as the English ‘black’) and ranging across the full breadth of Row I, containing a wide variety of dark shades:

Figure 7, the maximum visual range of vukö/avûko, with the focal point located at J0

This wide distribution across the darker hues of the Munsell Palette is again typical of Stage II languages in BCT theory (see Figure 5). It is also noted by Taber (1965), who describes vukö as “black, but also includes darker shades of blue, green, violet, and even brown as well as gray – reduplicated, it means pitch black”. The Sango translation of the Bible variously uses vukö/avûko to refer to darkness and lack of light in general, as well as to objects with black colouring. For example:

- Agbadola ni amu ndö ti sese kue si ndö ti sese ni avuko

PLU+locust ᴅᴇᴛ SM+take place ʟɪɴᴋ earth all then place ʟɪɴᴋ earth ᴅᴇᴛ SM+black

vukongo

blackness

“For they covered the face of the whole earth, so that the land was darkened” (SBC 2010 Exodus 10:15)

- Fadeso tere ti ala avuko ahon pindiri ti ngbonda ti tawa

now body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+black exceeding soot ʟɪɴᴋ bottom ʟɪɴᴋ pot

“But now they are blacker than soot” (SBC 2010 Lamentations 4:8)

- mbi yeke kanga le ti nduzu, mbi yeke sara si le ti

1SG be hide appearance ʟɪɴᴋ sky 1SG be do so that appearance ʟɪɴᴋ

atongoro avuko

PLU+star SM+black

“I will cover the heavens and darken their stars” (SBC 2010 Ezekiel 32:07)

(10) ataa so vuko kua ti tere ayeke daa pepe

even ʀᴇʟ black hair ʟɪɴᴋ body SM+be there ɴᴇɢ

“and there is no black hair in it” (SBC 2010 Leviticus 13:31)

Uniquely among Sango’s three BCTs, avûko was never used by our informant as the basis for a derived colour term in the construction avûko töngana… , although this may simply be the result of a lack of data. In the Bible, only a single example of avûko being used as the head verb for a derived colour term could be found, being:

(11) nzoroko ni abe tongana wâ, avuko tongana le ti nduzu si ayeke

colour ᴅᴇᴛ SM+red like fire SM+black like appearance ʟɪɴᴋ sky and SM+be

nga tongana sufre

also like sulphur

“fiery red, dark blue, and yellow as sulphur” (SBC 2010 Revelations 9:17)

3.1.3 Bengbä/Abe (‘ʀᴇᴅ’)

The maximum range of bengbä/abe (defined by the Taber dictionary (1965) as “a color term covering primarily red, orange, reddish brown, and the more intense, deeper shades of yellow” and by the SIL dictionary (2017) as “red, pink, orange, red-brown”) stretches far beyond the English colour term ‘red’ and beyond the typical boundaries expected of the ʀᴇᴅ term in languages with a larger number of BCTs, extending from light shades of purple on one extreme to pale greens on the other. However, as a distribution for a ʀᴇᴅ term in a Stage II language with only three BCTs, bengbä/abe again largely corresponds to the boundaries expected by Berlin & Kay (1969), and its focal point (G3) is an almost exact match with the expected ʀᴇᴅ focal points from the World Color Survey, which were clustered adjacent to G2 (Kay et al. 2009):

Figure 8, the maximum visual range of bengbä/abe, with the focal point located at G3. It should be noted here that there is evidence from derived colour terms that bengbä/abe has a distribution slightly broader than is indicated here, particularly concerning the inclusion of lighter shades of green (see Sections 3.2.1, 3.2.4 and 3.2.6).

Abe was the most productive of the BCTs in terms of serving as the head verb for derived colour terms; out of 25 derived colour terms mentioned by our informant, 11 were formed with the construction abe (töngana)…. Descriptions of colours on the peripheral range of bengbä/abe (such as yellows, oranges, light greens, and browns) were generally referred to using variations on this construction (as detailed throughout Section 3.2), although our informant also referred to peripheral shades of bengbä/abe using abe alone on several occasions, independently referring to his own skin colour, the skin colour of a Caucasian student, a golden plaque, and a shade of orange (E3) using only abe, without any additional modifiers.

Based on its usage in the Sango Bible translation, abe also appears to be polysemous, with additional senses referring ripeness (a common colexification in Western and Central African languages (Segerer & Vanhove 2021)) and anger:

(12) Tongana ale ti kobe ni abe awe

when PLU+eye ʟɪɴᴋ food ᴅᴇᴛ SM+red/ripe ᴘᴀsᴛ

“But when the grain is ripe” (SBC 2010 Mark 4:29)

(13) le ti ala abe na ngonzo

face ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+red ᴘʀᴇᴘ anger

“[all in the synagogue] were filled with wrath” (SBC 2010 Luke 4:28)

3.1.4 Nominalised BCTs

The nominalised forms of the three Sango BCTs are all constructed with the suffix -ngö (vüköngö, vürüngö, and bëngö), although the SIL dictionary also provides vüköngö-ndo as an alternative nominalisation for vukö. All three of these nominalised forms can be used immediately following their respective verbal forms in a pseudo-reduplicative construction which appears to emphasise colour intensity, particularly when either an intense colour would not otherwise be expected, or when numerous colours (or shades of the same colour) with varying intensity are described in sequence. For example:

(14) buruma amu tere ni kue; le ti buruma ni avuru vurungo.

leprosy SM+take body ᴅᴇᴛ all appearance ʟɪɴᴋ leprosy ᴅᴇᴛ SM+white whiteness

“the skin was leprous—it had become as white as snow” (SBC 2010 Exodus 4:6)

(15) Ayeke mu lo na popo ti azo so angba na fini, abi

SM+be take 3SG ᴘʀᴇᴘ space ʟɪɴᴋ PLU+person ʀᴇʟ SM+remain ᴘʀᴇᴘ life SM+launch

lo na ndo ti akuâ so avuko vukongo

3SG ᴘʀᴇᴘ place ʟɪɴᴋ PLU+corpse ʀᴇʟ SM+black blackness

“He is driven from light into the realm of darkness” (SBC 2010 Job 18:18)

(16) Na peko ti lo, ambeni mbarata ni ayeke daa so tere ti ala abe

ᴘʀᴇᴘ back ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG ᴘʟᴜ.ɪɴᴅᴇғ horse ᴅᴇᴛ SM+be there ʀᴇʟ body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+red

bengo, tere ti ala avuru tuuu si tere ti ala avuru vurungo.

redness body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+white translucent and body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+white whiteness

“Behind him were red, brown [or speckled] and white horses.” (SBC 2010 Zechariah 1:8)

With abe bëngö in particular, this construction does not necessarily seem to imply intensity around the focal point of the colour term; rather, it indicates an intense variety of any hue within the range of bengbä; for example, the Bible contains instances of the construction being used to refer to both “red” and “purple”, depending on context:

(17) Zo so ayeke diko mbeti so si lo fa na mbi nda ni, fade ayeke yu

person ᴅᴇᴍ SM+be read book ᴅᴇᴍ and 3SG show ᴘʀᴇᴘ 1SG source ᴅᴇᴛ ғᴜᴛ SM+be wear

na lo bongo ti agbia so abe bengo

ᴘʀᴇᴘ 3SG clothes ʟɪɴᴋ ᴘʟᴜ+king ʀᴇʟ SM+red redness

“Whoever reads this writing, and shows me its interpretation, shall be clothed with purple” (SBC 2010 Daniel 5:7)

(18) Na peko ti lo, ambeni mbarata ni ayeke daa so tere ti ala abe

ᴘʀᴇᴘ back ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG ᴘʟᴜ.ɪɴᴅᴇғ horse ᴅᴇᴛ SM+be there ʀᴇʟ body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+red

bengo, tere ti ala avuru tuuu si tere ti ala avuru vurungo.

redness body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+white translucent and body ʟɪɴᴋ 3PL SM+white whiteness

“Behind him were red, brown [or speckled] and white horses.” (SBC 2010 Zechariah 1:8)

3.2 Sango Derived Colour Terms

As is the case in virtually all languages, Sango has a far greater variety of derived colour terms than basic ones; for example, out of the twenty randomly selected colour chips shown to our participant, only six of them were described using solely BCTs. Sango derived colour terms typically stem from comparisons with natural phenomena, and in this capacity, they are highly productive and varied in terms of their exact compositional referents, with our informant often providing several different derived colour term descriptions for the same Munsell Palette chip when asked to describe it several days apart. However, despite these apparent compositional idiosyncrasies, syntactically, the encoding of these colour terms is exceedingly systematic. Out of the 25 derived colour terms provided by our participant, all but one followed one of three constructional patterns:

abe/avuru/avûko töngana… (‘[it] is bengbä/vurü/vukö like…’)

(19) Tongana siokpari ti ala abe tongana mene

though sin ʟɪɴᴋ 2PL SM+red like blood

“Though they [your sins] are red as crimson” (SBC 2010 Isaiah 1:18)

angbâ (töngana) … (‘remains like …’)

(20) Couleur nî angbâ töngana wên

colour ᴅᴇᴛ SM+remain like metal

“The colour is grey” (lit. ‘the colour remains like metal’)

akpa … (‘resembles …’).

(21) Le nî akpa kôbe tî kâsa

appearance ᴅᴇᴛ SM+resemble leaf ʟɪɴᴋ food

“The square is green” (lit. ‘the eye/surface resembles edible leaves’)

The sole apparent exception to this is the colour term tutûu (“blue”), which is consistently used following ayeke (to be):

(22) Bongö tî lo ayeke tutûu

clothes ʟɪɴᴋ 3SG SM+be blue

“Her clothes are blue”

3.2.1 ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ

Most colours described within the range of ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ are included in the distribution of bengbä/abe, although some lighter shades fall within the range of vurü/avuru. Although no BCT for ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ exists, the derived term abe töngana nzö (‘[it] is bengbä like maize’) can be used to refer specifically to the yellower shades within the range of bengbä, as can avuru töngana gozo (‘[it] is vurü like cassava’) for lighter yellows and beiges in the range of vurü (i.e. B12 on the Munsell Palette). Additionally, terms such as avuru kete (‘[it] is a little bit vurü’), avuru gï ze ([it] is only slightly vurü’) were used for light shades of ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ such as B2.

Figure 9, the maximum visual range of abe töngana nzö, with the focal point located at C9. Despite being a subordinate term to bengbä, as indicated by its head verb abe, abe töngana nzö has a distribution which reaches farther into the region of light green than our informant initially indicated on the Munsell Palette for abe (reaching column 13 in rows C and D, compared to 11 (see Section 3.1.3)).

An additional term for ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ is found in the SIL dictionary (2017), kambîri (“orange (color); yellow; hot, yellow-orange palm oil”); this term, however, was only used by our informant once (after being prompted with the dictionary gloss), and its exact range remains poorly defined. It can thus be ruled out as a BCT, on account of both its apparent lack of psychological salience and its compositional nature (being that it is a term for the orangish substance of palm oil).

(23) Bongö tî kambîri

clothes ʟɪɴᴋ orange

“Orange clothes”

3.2.2 ɢʀᴇᴇɴ

Aside from the light, yellowish shades included in the peripheries of bengbä/abe, most of the hues included in the range of ɢʀᴇᴇɴ fall outside of the distributions of any of Sango’s three BCTs. Rather, ɢʀᴇᴇɴ shades are typically expressed through the highly productive construction akpa kôbe tî … (‘resembles the leaf of …’), with specific varieties of plants being substituted into the construction to refer to specific shades of green. For example, a general term for darker shades of ɢʀᴇᴇɴ is akpa kôbe tî kâsa (‘[it] resembles edible leaves’), while a lighter ɢʀᴇᴇɴ may be referred to as akpa kôbe tî mângo (‘[it] resembles mango leaves’).

Figure 10, the maximum visual range of akpa kôbe tî kâsa, with the focal point located at H17

An additional term for ɢʀᴇᴇɴ is found in the SIL dictionary (2017), being ngû-ngunzä (lit. ‘water of cassava [leaf]’). Although our own informant agreed with this term, identifying the focal point as H12, he insisted that the term was more properly said ngû tî ngunzä, and that ngû tî gozo (‘water of cassava’) was equally common. This ‘water of …’ colour term construction is fairly common across Western and Central African Niger-Congo languages, forming a “clear cluster” geographically (Segerer & Vanhove 2021); however, in Sango, our informant only provided or verified three ngû tî … colour terms, being the aforementioned terms for ɢʀᴇᴇɴ and ngû tî karakânzi (‘water of sorrel’), a term for maroon described in Section 3.2.6.

3.2.3 ʙʟᴜᴇ

The most common term given for ʙʟᴜᴇ (especially lighter hues) was angbâ/akpa (töngana) le tî ndüzü (‘[it] looks like/resembles the sky’). Darker ʙʟᴜᴇ colours were often simply referred to as avûko, although combined instances of le tî ndüzü avûko or avûko töngana le tî ndüzü were seen as well (see Section 3.1.2):

(24) Fade ala yeke mu bongo so nzoroko ni kue akpa le ti le

ғᴜᴛ 2PL be give clothes ʀᴇʟ colour ᴅᴇᴛ all SM+resemble appearance ʟɪɴᴋ surface

ti nduzu

ʟɪɴᴋ sky

“Make the robe [of the Ephod] entirely of blue cloth” (SBC 2010 Exodus 28:31)

Figure 11, the maximum visual range of le tî ndüzü, with the focal point located at D28. Our informant also commented that E28 and F28 were equally fitting as focal points.

As mentioned in Section 3.2, extant dictionaries also provide the term tutûu for ʙʟᴜᴇ. However, although tutûu is the only word for ʙʟᴜᴇ mentioned in current dictionaries, our own informant did not mention the word at all until specifically prompted to do so by being shown its dictionary entry; similarly, another Sango speaker who was observed (but not fully tested) in the process of data collection was confused when asked to describe the colour of a blue dress in a photograph, and did not provide the answer tutûu until prompted to do so with the same dictionary entry. This lack of psychological salience seems to disqualify tutûu from BCT status, as does its apparent etymological relationship to tûutûu, a word for a bluish-grey feathered cuckoo bird.

3.2.4 ʙʀᴏᴡɴ

Although most shades of ʙʀᴏᴡɴ lay outside of the boundaries of bengbä/abe delineated in our experiment with the Munsell Palette, our informant consistently referred to derived ʙʀᴏᴡɴ terms using the construction abe töngana … (‘[it] is bengbä like …’). For example, the two most consistent derived colour terms for ʙʀᴏᴡɴ provided by our informant, abe töngana sêse (‘[it] is bengbä like earth’) and abe töngana mbütü ([it] is bengbä like sand’) had their focal points at H9 and F10 respectively, both outside the putative range of bengbä/abe.

Figure 12, the maximum visual range of abe töngana sêse, with the focal point located at H9. Note that, much like with abe töngana nzö, abe töngana sêse stretches farther into green and brown hues than was initially designated by our informant on the Munsell Palette.

Our informant also provided several terms for ʙʀᴏᴡɴ which did not require the verb abe, namely, akpa ülëngö kôbe (‘[it] resembles dry leaves’) with a focal point at H8, and akpa kpekpe kâsa (‘[it] resembles rotten food’) with a focal point at H13. Aside from bengbä, extant dictionary sources provide only one Sango word for ʙʀᴏᴡɴ, being bevu, however, our informant insisted that this was a Yakoma word, rather than a ‘true’ Sango word.

3.2.5 ᴘɪɴᴋ

The entirety of the expected distribution of ᴘɪɴᴋ falls within the range of bengbä/abe, and as such few derived terms exist in Sango specifically to describe it. However, the use of certain modifiers with abe can serve to specify ᴘɪɴᴋ as opposed to the more focal shades of bengbä/abe; for example, abe avuru (‘[it] is pale bengbä), abe töngana kä tî wâlï (‘[it] is bengbä like a vagina’), and abe töngana kä (‘[it] is bengbä like a wound’) were all given, although our informant later retracted the third term on the basis that it referred to a much darker, scab-like colour, rather than ᴘɪɴᴋ.

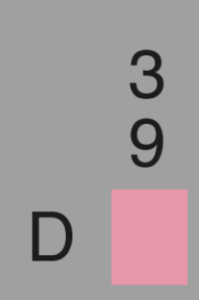

Figure 13, the focal point for abe töngana kä tî wâlï, D39. Our informant did not provide a range for this term, and implied that its use was not widespread.

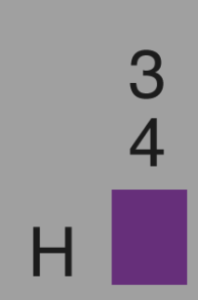

3.2.6 ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ

Most shades of ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ are included within the visual range of bengbä/abe, and as such, similarly to ᴘɪɴᴋ, descriptors for ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ as opposed to ʀᴇᴅ were typically constructed by pairing abe with a modifier of some kind for comparison, such as abe töngana aubergine (‘[it] is bengbä like eggplant’). Additionally, some lighter shades of ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ are included in the peripheries of angbâ/akpa (töngana) le tî ndüzü (see Section 3.2.3). Finally, the SIL dictionary provides karakânzi (given by our informant as abe töngana karakânzi (‘[it] is bengbä like sorrel’), or ngû tî karakânzi (‘water of sorrel’)) with the definition “purple, maroon”, however this term was more closely identified by our informant with the latter shades of burgundy or darker ʀᴇᴅ hues (with a focal point at I2), rather than with ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ.

Figure 14, the focal point for abe töngana aubergine, H34. Our informant again did not provide a range for this term.

3.2.7 ɢʀᴇʏ

The Sango term for ɢʀᴇʏ was consistently provided by our informant as angbâ töngana wên (‘[it] appears like metal’), with this referring to shades of ɢʀᴇʏ between D0 and H0 on the Munsell palette, with darker shades being referred to as vukö, and lighter shades being vurü (see Section 3.1.1). Extant dictionaries also provide mbürüwâ (“the color gray; cinders”) as a term for grey, however, our informant was unaware of this term, and interpreted it as referring to palm nuts (mbûrü), which he associated with a “bright, reddish orange”.

Figure 15, the maximum visual range of angbâ töngana wên, with the focal point located at F0

3.2.8 ᴏʀᴀɴɢᴇ

As previously mentioned, ᴏʀᴀɴɢᴇ is entirely included within the distributed range of bengbä/abe, with terms used to describe it in contrast to focal shades of bengbä/abe including

abe töngana papaye (‘[it] is bengbä like a papaya’), abe töngana wâ (‘[it] is bengbä like fire’), and the aforementioned kambîri. Additionally, abe töngana orânzi (‘[it] is bengbä like an orange’) was recognised by our informant as comprehensible, but not as a term with which he had any familiarity.

Figure 16, the maximum visual range of abe töngana papaye, with the focal point located at D6

3.3 Cross-Linguistic Comparison

As previously mentioned, the focal points and total distributions of Sango’s three BCTs closely follow cross-linguistic expectations, based on Berlin & Kay (1969) and the later World Color Survey (2009). Additionally, the focal points of some of Sango’s more common derived colour terms align with expected focal points of similar, basic colour terms in languages with a greater number of BCTs. For example, if one is to take abe töngana nzö as ʏᴇʟʟᴏᴡ, akpa kôbe tî kâsa as ɢʀᴇᴇɴ, le tî ndüzü as ʙʟᴜᴇ, abe töngana sêse as ʙʀᴏᴡɴ, angbâ töngana wên as ɢʀᴇʏ, abe töngana aubergine as ᴘᴜʀᴘʟᴇ, abe töngana kä tî wâlï as ᴘɪɴᴋ, and abe töngana papaye as ᴏʀᴀɴɢᴇ, all of which being terms given by our informant in the random colour chip test and verified with at least some confidence in the full palette test, the focal points of these Sango colour terms map to the focal points of the 20 languages surveyed in Berlin & Kay (1969) and to the 110 unwritten languages surveyed in the World Color Survey as follows:

Figure 17, focal points of basic and commonly derived colour Sango colour terms compared with the focal points of BCTs in twenty typologically unrelated languages from Berlin & Kay (1969)

Figure 18, focal points of basic and commonly derived Sango colour terms compared with the averaged focal points of BCTs in 110 unwritten languages from the World Color Survey (Kay et al. 2009)

Conclusion

Like many Niger-Congo languages in Western and Central Africa, Sango has three basic colour terms, vukö/avûko (‘black’), vurü/avuru (‘white’), and bengbä/abe (‘red’), whose maximum visual extensions and focal points closely correspond to expected cross-linguistic norms (Berlin & Kay 1969; Kay et al. 2009). Aside from these BCTs, Sango has an extensive and productive inventory of compositional, derived colour terms, typically encoded as verb phrases using either one of the three verbal BCTs (avûko, avuru, or abe) or the verbs angbâ (töngana) or akpa paired with a comparison or modifier of some kind. To a degree, many of these derived colour terms seem idiosyncratic, and there was relatively little overlap between the derived colour terms listed in existing dictionaries, those provided by our informant, and those found within Sango translations of texts such as the Bible. Nonetheless, this investigation has served as a mere primer for studies into Sango colour terminology and as a repository for existing data points; more comprehensive original studies would require a greater number of native Sango-speaking participants, experimentation on monolingual speakers, and a broader variety of Sango texts for corpus analysis.

References

Berlin, Brent & Paul Kay. 1969. Basic Colour Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Gladstone, William E. 1858. Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age. Oxford, OXF: Oxford University Press.

Kay, Paul & Chad McDaniel. 1978. The Linguistic Significance of the Meanings of Basic Color Terms. Language, 54. doi:10.2307/412789.

Kay, Paul. 2006. Methodological issues in cross-language color naming. In: Jourdan, Christine & Kevin Tuite. (eds.) Language, Culture and Society, 115–134. Cambridge, CAM: Cambridge University Press.

Kay, Paul, Brent Berlin, Luisa Maffi, William Merrifield & Richard Cook. 2009. The World Color Survey. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications

Kay, Paul & Luisa Maffi. 2013. Number of Non-Derived Basic Colour Categories. In: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. (Available online at http://wals.info/chapter/132, Accessed on 2022-03-21.)

Levinson, Stephen C. 2001. Yélî Dnye and the Theory of Basic Color Terms. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 10(1):3-55

Lucy, John A. 1997. The scope of linguistic relativity: an analysis and review of empirical research. In: Gumperz, John J., Stephen C. Levinson (eds.) Rethinking Linguistic Relativity. Cambridge, CAM: Cambridge University Press.

MacLaury, Robert. 1997. Color and Cognition in Mesoamerica: Constructing Categories as Vantages. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press

Rivers, William H. 1901. Primitive Color Vision. Popular Science Monthly, 59:44-58

Samarin, William J. 1963. A grammar of Sango. Hartford Seminary Foundation, Hartford, CT

Sampson, Geoffrey. 2013. Gladstone as linguist. Journal of Literary Semantics. 42:1–29. doi:10.1515/jls-2013-0001

Saunders, Barbara. 2000. Revisiting basic color terms. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 6(1):81–99. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.00005

Segerer, Guillaume & Martine Vanhove. 2021. Areal patterns and colexifications of colour terms in the languages of Africa. Linguistic Typology, 2021. doi:10.1515/lingty-2021-2085

SIL, ILA. 2017. “Mini Sango Dictionary.” Webonary.org. SIL International. Retrieved 1/4/22, from https://www.webonary.org/sango/overview/copyright/?lang=en.

La Société Biblique de Centrafrique. 2010. Mbeti ti Nzapa – Tënë so amu fini. La Société Biblique de Centrafrique, Bangui, CAR

Taber, Charles R. 1965. A dictionary of Sango. Hartford Seminary Foundation, Hartford, CT